Imagine an Ontario pedestrian signal that delivers the same high-visibility “stop-until-cleared” red phase you see in a US-style HAWK beacon, but fits the middle ground between a pedestrian crossover (PXO) and an intersection pedestrian signal (IPS). I was recently inspired by a presentation at ITE Canada by Trevor Demerse, entitled Built in a Flash: A Pedestrian Hybrid Signal Pilot Project in BC and thought that this would be an interesting idea to explore here in Ontario.

The intent of this article is not to advocate for the implementation of a pedestrian hybrid signal (PHS) in Ontario. Instead, consider this article an exploration of the PHS treatment. Is it possible in Ontario, based on current legislation, regulations, and the Ontario Traffic Manual (OTM)? What is the benefit vs. risk of the PHS compared to more conventional PXOs or IPSs?

Background: BC’s PHS Pilot

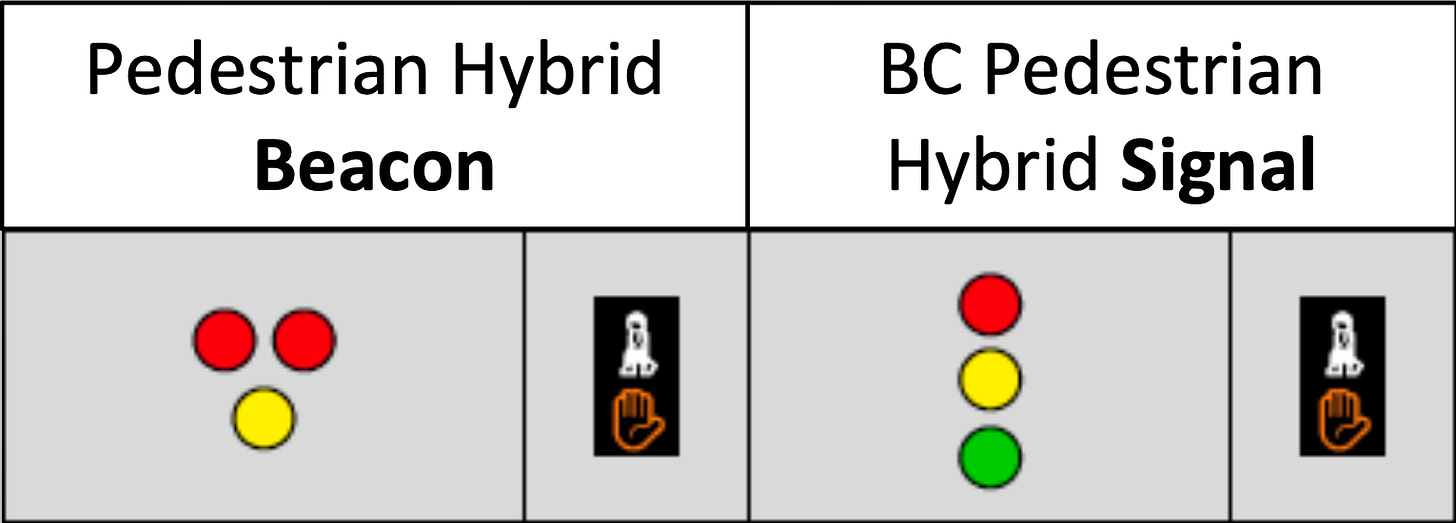

BC’s PHS pilot blends elements of the US-style Pedestrian Hybrid Beacon (HAWK) with BC’s existing beacon-only pedestrian signals. The operation consists of:

Inactive: Flashing green on the main street, typical for BC pedestrian signals.

Transition: Solid green on the main street, indicating a change is about to occur.

Yellow Change: Typical for every signal.

Red Clearance: “All Red” (AR) before the crossroad walk phase.

Walk: Crossroad WALK interval.

Pedestrian Clearance: Flashing Don’t Walk (FDW) with main street transitioning to “wig-wag” (i.e. alternating) red light flashing, similar to what you’d see at a railway crossing.

Buffer Time: Solid Don’t Walk with main street maintaining “wig-wag” flashing until the clearance interval is complete.

The pilot PHS approach differs from the HAWK beacon in two key elements:

The PHS looks like an IPS configuration, so it could be easily upgraded to full IPS functionality when warranted.

The PHS is NOT dark when inactive, avoiding confusion and maintenance service calls due to confused drivers.

The pilot PHS involved the following location and geometry context:

Site: Mid-block crossing on West 16th Avenue at Hampton Place in Vancouver, adjacent to UBC.

Configuration: Two-stage crossing across two lanes each way, with a central median refuge. Seen as an ideal candidate location, considered a mid-block crossing with lower-risk turning movements

Traffic environment: Posted speed limit of 50 km/h, high vehicle volumes and frequent transit service.

Pedestrian context: Connects a residential neighbourhood (south side) to an elementary school (north side), generating sustained pedestrian demand and long wait times under the previous PXO treatment.

Key performance outcomes and observations from the pilot include:

Pedestrian actuation rates increased to 70% (+30%), which was an improvement over the PXO previously installed at that location.

Driver compliance on “wig-wag”, alternating red clearance was 50% with drivers correctly stopping, then proceeding when safe to do so once the crosswalk was clear.

Vehicle queues in the AM peak period were significantly reduced, ensuring that buses were able to more reliably access the university campus.

Video-based observations for two days (three months post-implementation) additionally revealed:

62 instances of PHS users (i.e. pedestrians, bicycles, etc.) illegally entered traffic, forcing vehicles to yield.

6 instances of red light running and 5 instances of failing to yield on flashing red (i.e. “wig-wag”).

Over 80% of cyclists ran the main street red light instead of yielding to crosswalk users.

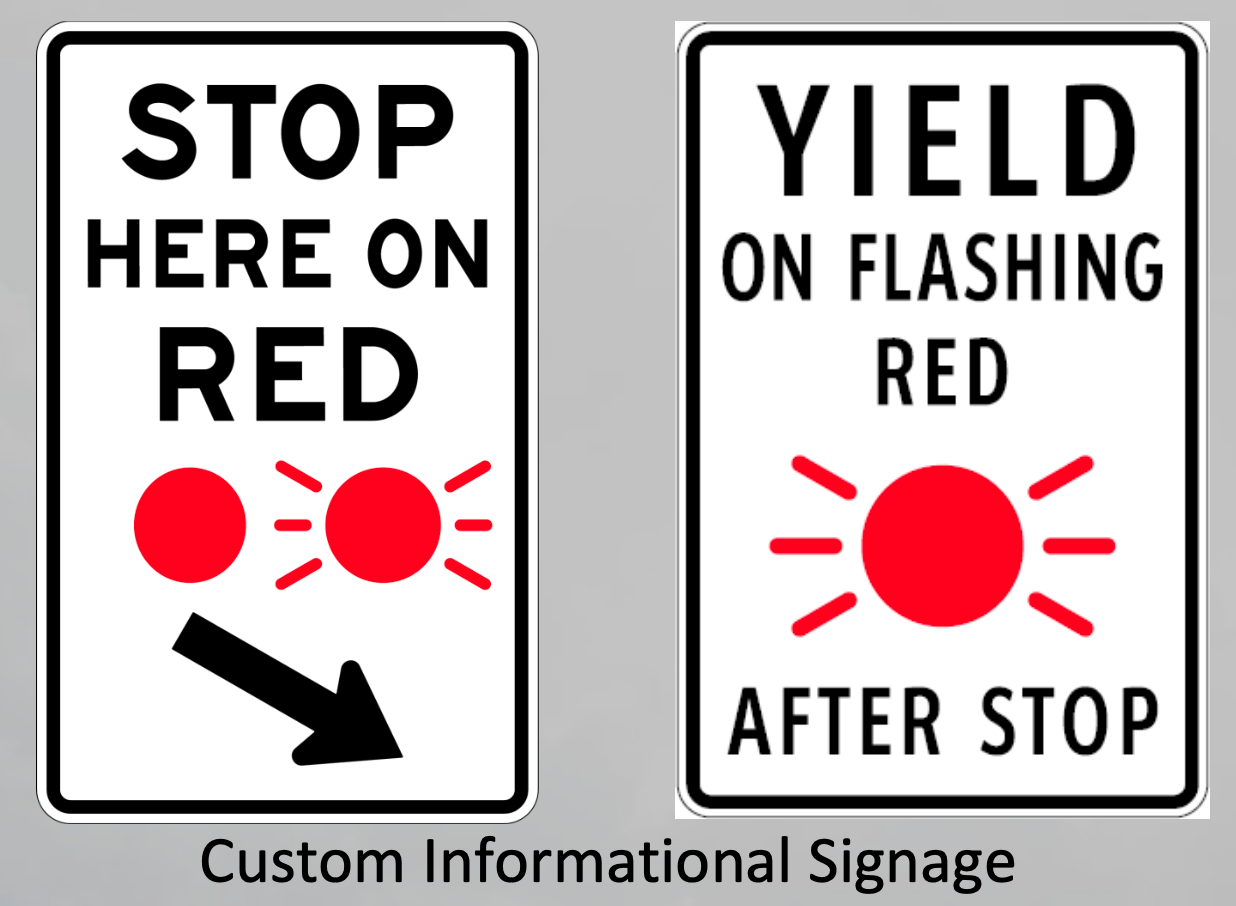

Further, custom PHS signage was installed to illustrate proper behaviour to drivers.

Giving full credit, the ITE Canada presentation is currently available on PheedLoop.

Ontario Regulatory and Warrant Context

So, where does this leave Ontario? The legislative and regulatory framework would likely have more challenges than BC to support a PHS. Further, the “flashing green” display shown in BC has the meaning of an advance left to many older drivers in Ontario, so it would likely need to be eliminated. However, the “wig-wag” alternating flashing red display would require codification in Ontario law.

Modified for the Province of Ontario jurisdiction, a PHS treatment might look and operate similarly to the following GIF animation:

Beginning with laws and regulations, the following would require further study and amendment:

HTA, Section 144(21): “Every driver approaching a traffic control signal and facing a flashing circular red indication shall stop his or her vehicle, shall yield the right of way to traffic approaching so closely that to proceed would constitute an immediate hazard and, having so yielded the right of way, may proceed.”

Broadly, this could be interpreted as supportive of a PHS. However, it does not specifically address this use case or functionality, so an amendment should be considered.

An amendment would need to formally legalize the “stop-then-go-if-clear” behaviour during the flashing red phase of a PHS.

O. Reg. 626 generally deals with physical traffic signal displays. Since the proposed PHS is focused on how it operates, but is physically identical to an IPS, it is unlikely that an amendment is required here. However, this should still be reviewed and amended if required.

OTM Book 5, Regulatory Signs would require updating to establish appropriate PHS regulatory signage, similar to the custom BC pilot signage above.

OTM Book 12, Traffic Signals would require updating to specifically address the design and operations of the PHS treatment and touch upon potential warrant requirements.

OTM Book 15, Pedestrian Crossing Treatments would require updating to include the PHS in the hierarchy of treatments between the PXO and the IPS.

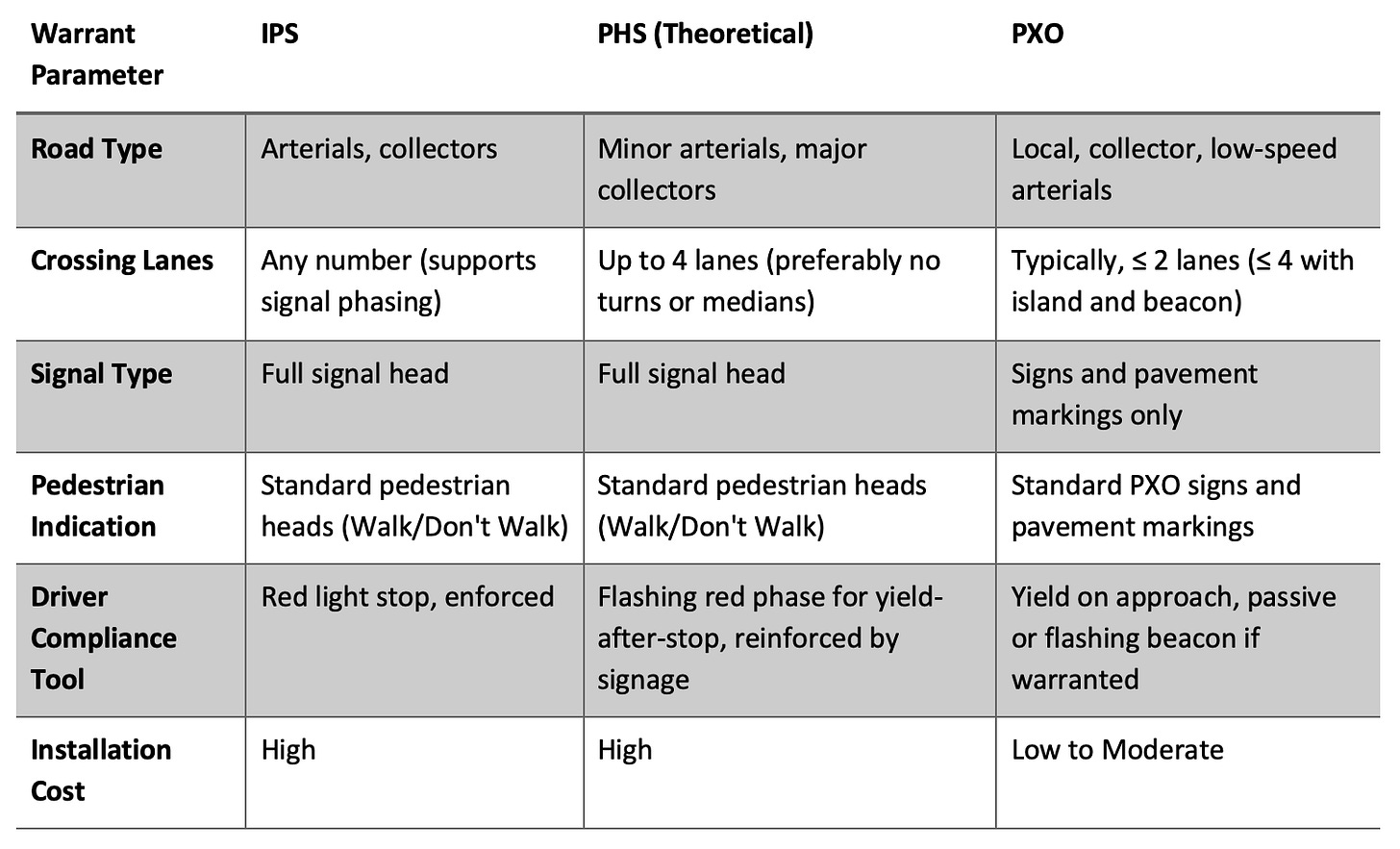

The table below speculates where the PHS might theoretically fit qualitatively between the PXO and IPS. However, these claims would need more scrutiny and due diligence before a standardized approach could be established.

As an alternative, a temporary legislative allowance or pilot framework may be more appropriate to explore a PHS implementation in Ontario.

Returning to the HTA, Section 228, Pilot Projects, several clauses allow for the creation of a regulatory framework supporting a PHS pilot. This was similarly applied under O. Reg. 306/15 for an automated vehicles pilot program, which has an expiry date. However, in the worst case, a PHS could be easily reconfigured into a typical IPS installation if unsuccessful.

§228(1): The province can launch pilot projects to test new traffic control ideas.

§228(2): Pilots can legally override existing traffic laws and regulations.

§228(4): Custom rules can be written specifically for how the pilot operates.

§228(6): Every pilot must have an expiry date within 12 years.

§228(7): If there’s a conflict, the pilot rules take priority over regular laws.

Discussion

Given all of the above considerations – legislation, pilot outcomes, and comparisons to existing Ontario treatments – the question remains: Is a Pedestrian Hybrid Signal (PHS) treatment worth pursuing?

There’s value in learning from other jurisdictions. BC’s pilot provides a compelling example of adapting established HAWK-style operational logic for the Canadian context. Experimentation with new treatments helps us better understand both operational efficiency and safety outcomes, especially in complex environments like mid-block crossings or locations with high transit demand.

However, I keep returning to the potential risks, particularly when considering non-compliance by the public with a PHS treatment.

Have HAWK beacons in the U.S. become broadly accepted? And if so, under what conditions? Are PHS-style treatments best suited for mid-block or two-stage crossings where turning conflicts are minimal and the geometry is more predictable? Jurisdictions like the UK have adopted similar mid-block concepts, allowing pedestrian clearance phases to operate concurrently with an advisory or cautionary main street phase, helping to reduce unnecessary driver delay while maintaining core safety principles. These types of compromises, when applied carefully, could help ease driver frustration and support transit without sacrificing pedestrian protection.

Still, the safety of pedestrians and vulnerable road users needs to remain paramount. Introducing a hybrid system like this, especially one unfamiliar to Ontario drivers, raises legitimate concerns around compliance and comprehension. From my own experiences implementing new or unfamiliar signal treatments in a jurisdiction, driver adaptation to new conditions is inconsistent. Even with uniquely distinguished and signed bicycle or transit signals, confusion and non-compliance have been regular challenges.

This leads to key implementation questions:

Can we effectively educate the public to ensure safe use of a PHS?

Or, will this become a high-risk, misunderstood signal operation that undermines compliance?

Can the operational and safety benefits seen in BC be replicated in Ontario, or are driver behaviours too different?

These questions deserve discussion, research, and piloting. If anything, BC’s work opens the door for Ontario to critically examine whether a hybrid approach like this could serve as a middle ground between a PXO and IPS, or whether the complexity outweighs the benefit.

Closing Thoughts

BC’s pilot shows that a PHS can improve compliance and reduce delays at crossings for both vehicles and pedestrians where an IPS is not fully warranted. However, Ontario’s regulatory landscape, driver expectations, and design standards are unique to our province.

So, is there room for a treatment that sits between a PXO and an IPS? Or, would introducing something unfamiliar create more confusion than benefit?

This isn’t a call to implement a PHS, but rather to ask the right questions and consider whether a PHS should be explored. Let’s open the conversation. Your feedback could help shape how (or if) something like this takes root in Ontario.

Would a PHS-style treatment fit anywhere in your transportation network? Could a PHS improve outcomes, or complicate enforcement and education? Is it worth piloting, or should it be left on the shelf? I’d love to hear your thoughts!